More than seventy years after the defeat of the popular front of Republicans at the hands of Franco’s Nationalists, public commemoration of Canada’s contributions to the Spanish Civil War remains limited. The list of Canadian veterans in the Peace Tower on Parliament Hill still makes no mention of the nearly 1600 volunteers who went to Spain, the 60th anniversary of the outbreak of the war passed without acknowledgement from Parliament Hill, and all monuments erected to the Canadian volunteers were conceived of and funded by grassroots efforts, or were gifts from the government of the People’s Republic of China.

The official silence by the Canadian government on the Canadian contributions to the Spanish Civil War is particularly striking when one considers that the volunteer response was disproportionately large for a country with a population as small as Canada’s. Canada was second only to France in the percentage of its population sent to Spain: this statistic is made all the more impressive when one considers France and Spain share a border, while Canada and Spain are separated by the Atlantic Ocean (Zuehlke 196). In the face of the substantial contributions of soldiers, journalists, medical personnel, and funds by the Canadian public, and of recent campaigns for official recognition by the Canadian people, the silence of the Canadian government can hardly be seen as accidental. The involvement of the government—and of the other liberal-capitalist democracies that would compose the Allies during the Second World War—in the suppression of leftist volunteers going to Spain does not fit the official narrative which maintains that liberal democracy and capitalism stand alone in direct opposition to right wing authoritarianism, fascism, and totalitarianism. Despite these claims, the arms embargo of the Spanish Republic by the liberal-capitalist countries, along with their tacit approval of the Nazi and Italian Fascist arming of Franco, can be counted among the most overlooked and reprehensive political and humanitarian failures of the 20th century. This combination of selective inaction and repression, as well as a continuing aversion to and fear of left-wing politics, mean that official acknowledgement of the Canadian contribution has been essentially non-existent. This is not to say that the efforts of Canadians went unnoticed. The groundswell of support for the Republican cause seen in the 1930s ensured the war and the International Brigades joined the canon of lost causes celebrated by leftists. Public commemorations, especially in the traditional forms of Remembrance Day ceremonies and war memorials, have only been possible due to the dedication of veterans, their family members, those interested in working class history, and leftists and anti-fascists familiar with the Spanish Civil War.

There were fears that the Communist Party of Canada had sent workers to Spain to be trained to later return to Canada and form the nucleus of an armed uprising. A 1937 letter from the RCMP Commissioner to the undersecretary of state for external affairs reads in part: “it is felt that these youths are being sent to Spain largely for the sake of gaining experience in practical revolutionary work and will return to this country to form the nucleus of a training corps” (Petrou 171). It would seem that any officially sanctioned public celebration of anti-fascist action by left-wing groups is unlikely under the “traditional” governing parties of Canada, as a proper explanation of the governmental repression of these anti-fascists would bring into focus the fascist sympathies of some of the leaders of the period, and would instead be celebrating revolutionary leftists. Instead, the official focus on Canadian contributions to the First and Second World Wars, the Korean War, and a variety of “peacekeeping” missions involves less exposure of the past anti- democratic actions of the Canadian government. Such commemoration can also cast these wars as indicative of Canadian commitment to the preservation and spread of democracy, even when this was not always the case. Regardless of the reasons, repression and surveillance of veterans continued for years, and official public commemoration was non-existent until the 1990s and early 2000s.

Today, Canada has at least three memorials dedicated to the Canadian volunteers and the veterans of the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion. One is located in Ottawa, Ontario, one is located in Toronto, Ontario, and the other is in Victoria, British Columbia. There is also a plaque dedicated to Manitoban volunteers on an exterior wall of the Winnipeg City Hall. All three of the full size monuments are located in peculiarly prominent and distinguished places in their respective capital cities, despite their celebration of a cause that was politically unpopular for so long. In Victoria and Toronto, the monuments are within meters of the respective parliament buildings. In Ottawa, the national monument to the Mac-Paps can be found on Sussex Drive alongside other war memorials, only a few minutes by foot from the Parliament Hill and the Prime Minister’s residence. Despite the prominent placements of these monuments, the Foreign Enlistment Act—the law that threatened the citizenship of the volunteers—can be found in the Criminal Code of Canada.

In Victoria, the monument, entitled “Spirit of the Republic,” can be found across the street from the BC Legislature. It stands in a grove of trees beside the Confederation Garden Court at the intersection of Menzies Street and Belleville Street. It consists of a large metal statue of a woman, the embodiment of the “Spirit of the Republic.” A pamphlet produced for the commemoration of the dedication explains the symbolism of the statue:

The sculpture is identifiably Spanish with its Basque cap and crown (representing Spain’s regions and architecture), the rope sandals (alpargatas) on her feet, and the laurel wreath of the Spanish Republic held in her hand. The lovely figure portrays the strength, dignity, determination and beauty of a people who aspired to establish a democratic government. Jack Harman[, the sculptor of the piece,] has captured in her face the sadness of this slow victory at such a high cost. The dove of peace in her left hand is representative and characteristic of all nationalities and people who desire peace and democratic governments. (“Mackenzie Papineau Battalion Ceremony”)

Unlike many other war memorials, “Spirit of the Republic” is sculpted to represent ideals of democracy and peace, and is not a representation of a military commander or group of soldiers. This seems appropriate given the often political and ideological motivations of the volunteers. The sculpture, especially the dove, captures the idea that they were internationalists, risking their lives to resist fascism and authoritarianism in a country to which most volunteers had no personal connection. To the left of the statue are a number of metal plaques fixed to waste-high stop pillars emblazoned with the emblem of the International Brigades, some flowers, and a clenched fist. The pamphlet states:

The basalt pillars were chosen because of their similarity to rock formations in the Ebro Sector in Spain ... They symbolize the rough ground of the battlefields of Spain and the lack of cover encountered by the ill-equipped Canadian volunteers. Three of the pillars are arranged in a “V” shape to symbolize the eventual victory of the Spanish republic, after 45 years of dictatorship, upon the death of General Franco in 1975. These three columns each have a bronze medallion affixed to them: the emblem of the Veterans of the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion, the dogwood blossom commemorating the British Columbia volunteers, and the emblem of the International Brigades whose volunteers came from 53 different countries.

Despite the pamphlet’s assertions, the Spanish Republic has yet to rise again. In 1975, Spain did return to democracy after King Juan Carlos, Franco’s successor, chose to dismantle the Francoist regime. The liberal-democratic parliamentary monarchy he established survives to this day.

A larger plaque is placed on the ground in front of the statue, explaining the nature of the Spanish Civil War and the contributions of the international volunteers, including the Mac-Paps. The monument’s text begins with a dedication, and some historical context:

This monument commemorates the gallant men and women of British Columbia and Canada who offered their lives to defend the principles of democracy and served as the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion of the International Brigades in defence of the Republic of Spain.

In July 1936, the opening shots of the Second World War were fired in Spain. Insurgent forces led by General Franco staged a rebellion to crush the democratically elected Government of the Spanish Republic. This treason was met with armed resistance by the people of Spain who rose to defend the New Republic. Thus the Spanish Civil War had begun which pitted the democracy embodied in the Spanish Republic against the fascism of the insurgent forces led by Franco, whose allies were the Fascist regimes of Hitler and Mussolini.

Against a backdrop of appeasement of Hitler, the policy of Non-Intervention, and arms embargoes against the Republic rendering it virtually defenseless, volunteers from 53 countries – who joined the International Brigades – went to Spain to defend democracy and resist the spread of fascism. They fought at the side of the infant Spanish Republic to defend the right of the Spanish people to choose, by election, their government.

The monument is sure to historicize the struggle in Spain, linking it to the better-known anti-fascist struggle that followed. By highlighting the involvement of Hitler and Mussolini’s militaries, a direct link is drawn between what is often seen as Canada’s most “legitimate” war and one of its least known. Movies, historical novels, and high school history classes have long advanced that the fascism and Nazism of the Axis powers were horrific ideologies, known for their cultivation of profound political inequality, their death squads, and their genocidal policies. Not only did the Spanish international volunteers fight these ideologies—some of them twice—but they also had the political awareness and foresight to resist fascism while their governments ignored or even courted it.

The remainder of the monument’s text focuses on the contributions of the Canadian volunteers, particularly those of the British Columbians:

Nearly 1600 Canadians volunteers – confronted by the Foreign Enlistment Act of 1937 enacted by the Canadian Government and facing criminal charges under the Act – joined in that struggle to defend the Spanish Republic and the democracy it embodied. One- quarter of those volunteers came from British Columbia. Members of the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion served with distinction, honour, courage, and valour on the battlefields of Spain during the Civil War, which raged from 1936 to 1939.

Over 600 volunteers in the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion were killed in Spain. These brave individuals are forever part of the earth of Spain. Many of the survivors of the Battalion who returned to Canada in 1939 endeavoured to join and did join the Canadian forces to fight with the Allies in World War II, which began six months later. Once again, they were fighting fascism. The fascist alliance of the Axis Powers was finally defeated in 1945.

The number and percentage of the dead reveals another aspect of the sacrifice of these volunteers. Poorly equipped compared to the Nationalist forces, the International Brigades were used as “shock troops,” and thrown up time and time again against dug-in professional soldiers who had the latest in air support, armoured vehicles, and artillery. Every year on Remembrance Day, the monument is the site of a sort of alternative remembrance ceremony, which takes a broad scope of remembrance. Art Farquharson is a musician who was involved in the fundraising for “The Spirit of the Republic,” and continues to be involved in the ceremonies each November. Farquharson wrote in an email, “Each year we gather at the ‘Spirit of the Republic’ on November 11th to share a microphone with citizens and their stories of hopes for peace and memories of their experience with war.” The memorial, then, acts not only as a concrete and permanent way of remembering the contributions of Canadians to the republicans in the Spanish Civil War, but also as a gathering place for continued conversation and reflection about both the war and conflict more generally.

Mark Zuehlke’s book, The Gallant Cause: Canadians in the Spanish Civil War 1936-1939 is indebted to the Toronto memorial to the Mac-Paps. The Gallant Cause owes its style—what Zuehlke calls “literary non-fiction”—to a late night visit to the memorial by the author. Zuehlke asserts that when writing literary non-fiction, “The details surrounding the characters, the actions they take, and the thoughts they have are all drawn as faithfully as possible from the historical record” (7). He writes:

The decision to use the literary non-fiction technique to tell the story of the Canadians in the Spanish Civil War was made that autumn night in Toronto as I sat before the Queen’s Park monument to the veterans. It seemed to me that, more than any other Canadian veterans of war, those who served in Spain had been denied the opportunity to have their experiences related. (8)

In this anecdote we see an example of the value of public remembrance: not only can a physical marker commemorating sacrifice be a place for solemn gathering, such as “The Spirit of the Republic” in Victoria, but such markers can also provide a place for individual reflection on a too-often ignored part of Canadian history.

The introduction to Zuehlke book describes the monument:

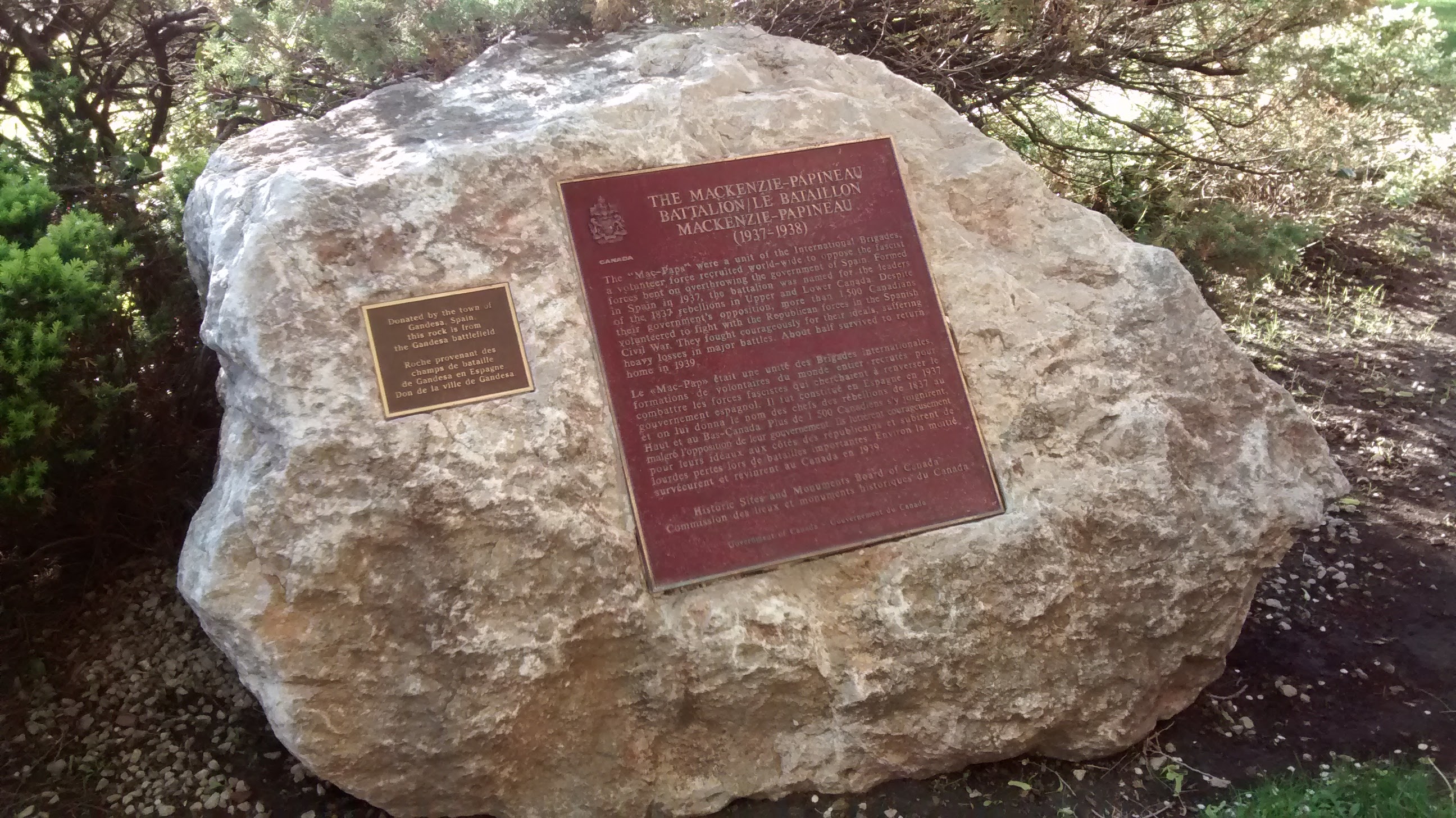

In Toronto’s Queen’s Park, a large rusty-white boulder sits between a huge monument to William Lyon Mackenzie, the rebel who inspired and led the doomed 1837 Upper Canadian Rebellion, and a narrow lane that provides vehicles with delivery access to the Ontario legislature. Thick shrubbery further shrouds the rock from the casual view of the passersby ... The stone was brought to Canada by Canadian Veterans of the Spanish Civil War. They had it collected it in the early 1990s from a battlefield near Gandesa in Aragon province. Here many men and women who volunteered to fight in the International brigades had perished. (1-2)

Toronto’s monument provides a particularly material link to the Spanish Civil War, taking Spanish soil to Canada. It also stands in a place similar to the British Columbian monument: it is right next to the provinces legislature, yet is hidden from view by shrubs. This monument to the contributions of the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion was funded and conceived of by the “Association of Friends and Veterans of the Mackenzie Papineau Battalion.” Permission to erect the monument was given by the provincial government in 1994 under the New Democratic Party of Bob Rae. The Friends and Veterans of the Mackenzie Papineau Battalion did not stop there. They were also responsible for the monument in Ottawa, which aims to have more national character.

Jules Paivio, who was ultimately the last surviving Canadian volunteer, directed the Ottawa monument’s construction. Paivio became an architect after returning to Canada. He would live to be the last surviving member of the Canadian volunteers, dying in 2013. The monument is far from a horse-mounted general or a stone obelisk. The design was chosen through a juried competition and was designed by Oryst Sawchuck of Sudbury, Ontario (Working TV). The Friends and Veterans of the Mackenzie Papineau Battalion have a description of the monument on their website: “The monument contains a 5 metre high sheet of corten steel out of which has been cut a silhouetted figure of a young man or Prometheus raising his clenched fist toward a cut-out Spanish sun.” Much less “traditional” in design and construction than the Victoria monument, the Ottawa memorial looks more like a modernist work of sculpture—with its planar surface and angular, asymmetrical qualities—than a bronze representation of a politician or general. The description continues, saying the statue is placed on a concrete pedestal with a plaque reading:

The Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion (The Mac-Paps), Canadian Volunteers of the International Brigades, Spain, 1936-1939

Canadians, 1,546 in number, left families, jobs and country to help the Spanish people defend democracy against the rise of fascism in the 1930’s. As part of the legendary International Brigades, a world-wide volunteer force from fifty-three countries, the Canadians were organized into the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion. It was named after the leaders of the 1837 rebellions against injustice in Upper and Lower Canada. Despite suffering heavy losses, many of the survivors continued to fight by serving in the Canadian armed forces in WWII. In their Promethean struggle for liberty, democracy and social justice, the Mac-Paps fought courageously for their ideals without thought of reward or fame.

Complementing this explanation of the international nature of the conflict are fifty-two stainless steel panels bearing inscriptions of the names of 1,546 Canadian volunteers that have been verified. Instead of a list of only the fallen, the monument takes inventory of all the Canadian volunteers. The names of the volunteers—absent from the Peace Tower and from the lists of those who received veterans benefits from the Canadian government—are enumerated in a way that makes them a feature of Ottawa landscape in a very tangible way.

Along the top of the wall runs an excerpt of the speech delivered by Dolores Ibárruri, the Spanish communist politican known for her rhetorical skills, to the departing International Brigadistas in 1938:

You can go proudly. You are history. You are legend. You are the heroic example of democracy, solidarity and universality. We shall not forget you, and when the olive tree of peace puts forth its leaves again . . . come back! And all of you will find the love and gratitude of the whole Spanish people who, now and in the future, will cry out with all their hearts: “Long live the heroes of the International Brigades!”

La Pasionaria’s invitation was accepted: when peace and democracy returned to Spain, many of the Brigadistas returned as well. The celebrations of the contributions of the International Brigades were also an inspiration for further commemoration in Canada. Joe Barrett, one of the organizers behind the construction of the Victoria monument, noted that the ceremony in Spain commemorating the 60th anniversary of the beginning of the war inspired commemoration internationally. He said in an interview with the Canada and the Spanish Civil War project, “One of the things those of us from Canada went home with was this sense that [we had to do] something to raise awareness about the ... whole story of the Mac-Paps. One way to do that is through memorials.” This resolution sparked a series of commemorative efforts, resulting in the monuments discussed above, and a private members bill in the House of Commons in an attempt to get the contributions of the Canadians officially recognized.

Public commemoration of the Canadian contribution to the Spanish Civil War also focuses on individuals, namely the medical efforts of Dr. Norman Bethune. In August 1972, following the normalization of Canadian diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China, the National Historic Sites and Monuments Board declared Bethune a Canadian of historical significance. It seems likely that some of the Canadian government’s newfound admiration for Bethune sprang from a desire to better relations with China, a country where the public commemoration of Bethune is unrivalled because of his work with Mao’s Eighth Route Army. In 1973, Bethune’s childhood home, a Presbyterian manse that later became a manse of the United Church of Canada in Gravenhurst, Ontario, was purchased by Parks Canada and became a national historic site. In 1976, it was opened to the public as a museum dedicated to Norman Bethune. In 2012, the federal government allocated $2.5 million to build a visitor’s centre at the Gravenhurst site. The site is home to a number of Bethune statues, ranging from portrayals of Bethune as a young lumberjack-teacher during his time with Frontier College, to Bethune in China performing an operation with an assistant, to Bethune standing on a rock, clasping his stethoscope. Many, including the Conservative Party’s own Rob Anders, viewed the move as an attempt to enhance relations with the People’s Republic of China (CBC). As mentioned before, the use of Bethune’s legacy as a tool to better Sino-Canadian relations is not a new strategy; in 1976, the People’s Republic of China gave a statue of Bethune to the City of Montreal. It was sculpted by Chinese sculptor Situ Jie, and was displayed for two years in the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. In 1978 it was revealed at Dorchester and Guy streets, in a public square named “Place Norman Bethune.”

Both the statue and the square were restored and rededicated in 2009, the 70th anniversary of Bethune’s death in China. The city allocated $3,000,000 to restore the square as a part of a larger project to revitalize the surrounding area, near Concordia University. In July 2000, a statue of Bethune was unveiled in Gravenhurst (Clarkson 199-200). Adrienne Clarkson, while serving as Canada’s 26th governor general from 1999 to 2006, attended the dedication ceremony for the statue. In 2009, Clarkson wrote a biography of Bethune for the “Extraordinary Canadians” series. A biographical treatment of a Spanish Civil War veteran by a former Governor General certainly does increase the circulation of the conflict in the national imaginary. Clarkson’s interest has other positive consequences for the remembrance of the Spanish Civil War: in his interview with the Canada and the Spanish Civil War project, Joe Barrett said, “Without the Governor General’s blessing, the national monument would not have happened. When it was inaugurated, she was front and centre, and there was a reception at [her official residence,] Rideau Hall.”

Denied official recognition of their contributions to the anti-fascist cause—and certainly denied benefits accorded to other Canadian veterans—by the Canadian government, Canadian veterans of the Spanish Civil War have instead only received recognition from the Canadian public. Upon return to Canada, the veterans were received warmly by the public, and very coldly by their government. As Misha Storgoff, a Canadian veteran of the International Brigades says in the 1975 National Film Board documentary, Los Canadienses: Canadians in the Spanish Civil War 1936-1939:

When we came back we didn’t come back as heroes, [but] we were recognized by the Canadian people. They met us at every station, but as far as the authorities were concerned they kept the trains locked from Montreal until we reached Toronto. When we reached Toronto, the government didn’t give any information but the people knew somehow and at every station there were groups of people yelling ‘Hurray for our boys!’ and ‘We’re glad your safe.’ ... It touches me even now. I cried ... Every time it is mentioned now I cry.

In Storgoff’s comments, we see a volunteer who deeply valued the recognition of the Canadian public. It seems more than likely that others would agree, as most were people of principle, motivated to preserve and enhance democracy and protect humanity from fascism. In light of the death of all remaining Canadian veterans, personal thanks of that sort are now impossible; all that remains is public commemoration of their anti- fascist struggle. That Storgoff and his comrades went unrecognized in their lifetimes is not surprising after one realizes that because of the number of socialist and communist volunteers and the historical suppression of the left in Canada, the official silence was all but inevitable. The Communist Party of Canada, responsible for sending the majority of the Canadian volunteers to Spain, was consistently harassed by the authorities, and for a time made illegal under Section 98 of the Criminal Code of Canada (Zuelke 3). Volunteers travelling to Spain risked losing their citizenship under the Foreign Enlistment Act of 1937, which criminalized service in foreign wars and was enacted to target Canadians joining the International Brigades. The volunteers were personally familiar with police repression, as most were workers—lumberjacks, miners, general labourers—or unemployed workers, who had fought for better conditions throughout the Great Depression. A great number of the 1600 Canadians who went to Spain had just a few years earlier antagonized Prime Minister R.B. “Iron Heel” Bennett with their “On-To-Ottawa” Trek, attempting to travel from the west coast to Ottawa by hopping trains. The trek was a continuation of the fight of the labour camp inhabitants for union wages, rather than the pittance granted to them by the government (On-to-Ottawa). The RCMP violently halted the march in Regina, where a peaceful protest by the trekkers was dispersed with police gunfire, wounding many in the crowd. While the majority of the trekkers headed home, Bennett and his cabinet held a token meeting with some representatives of the marchers (Liversedge 10). Later, five of these leaders of the march would fight in Spain (On-to-Ottawa). Of course, government repression of the working class did not begin or end there. Unemployed and homeless people were often charged with vagrancy and many were evicted from their homes, sometimes violently. Many Canadian volunteers were denied travel documents and found their passports stamped “Not valid for Spain.” Even after the war, veterans of the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion, or one of the numerous other battalions in which Canadian volunteers served, were subject to RCMP surveillance.

As the monuments draw visitors, the circulation of the stories of young men and women who left their homes to fight international fascism in a country entirely foreign to them will continue. For many of the international volunteers, the motivations that brought them to the Spanish Civil War were different from those associated with previous wars. Instead of international mercenaries flocking to a war for financial gain, professional soldiers being ordered into battle, or conscripts pressed into service by their government, thousands of politically motivated idealistic anti-fascists arrived to fight Franco and his Nationalist coalition. Canada’s monuments highlight the differences of the Spanish Civil War from most other armed conflicts in history by varying in design and construction from more traditional war memorials. Instead of commemorating a “great man,” the Victoria monument embodies the proclaimed ideals of the Spanish Republic. The Toronto monument focuses the viewer on the terrain of the battlefields on which the Canadian volunteers fought; the monument stands in for and represents the country—and in turn the struggle against fascism in Spain—with a transplanted piece of the landscape. The Ottawa monument elevates the struggle of the volunteers to a Promethean level, evoking the myth of fire stolen by Prometheus for the benefit of humanity, and the punishment he received for this deed. Also unlike other war memorials, the monuments differ wildly from each other despite commemorating the same war. Both the Victoria and Ottawa monuments are artistic representations of mythological or metaphorical figures, tied in some way to a struggle or to a democratic ideal. The Toronto piece is not necessarily a work deliberately representational of an ideal or myth, but instead draws meaning from its place of origin and from its displacement; when encountered, it forces a confrontation with a specific location and historical moment. An encounter with these monuments is, for many, a first encounter with the history of the Spanish Civil War. For many, the Spanish Civil War acts as a catalyst to a greater interest in radical politics, anti-fascism, or working class history. Public commemoration of the conflict can do much to inspire those who encounter the plaques and monuments to reflect on our particular historical moment, and the forces that have shaped our shared histories. The work of dedicated individuals has produced some beautiful and prominently placed monuments, but work remains to be done to secure the long sought-after official recognition. This recognition will not erase years of repression of leftists and surveillance of the volunteers, but it is a step in the right direction to note that despite what official discourses indicate, liberal democracies can and have violated rights, collaborated with fascists, and persecuted those who would see a more just and equitable world.

Works Cited

Barrett, Joe. Personal interview. 10 Aug 2014.

CBC News. “Tory MP calls Bethune memorial a ‘bow’ to China.” Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 14 July 2012. Web. 20 Aug 2014. http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/tory-mp-calls-bethune-memorial-a-bow-to-china-1.1204755

Farquharson, Art. “Re: Mac-Pap Memorial in Victoria.” Message to Kevin Levangie. Email. 8 Aug 2014.

Gregg, Mora. “Review: Mark Zuehlke, The Gallant Cause: Canadians in the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939.” The Manitoba Historical Society. Web. 13 Aug 2014. http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/mb_history/35/gallantcause.shtml

Harvey, Steve. “Mackenzie Papineau Battalion Monument.” Union Song. Web. 13 Aug 2014. http://unionsong.com/reviews/macpaps.html

Los Canadienses. Dir. Albert Kish. NFB: 1975. Film. https://www.nfb.ca/film/los_canadienses

“Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion Ceremony ‘Spirit of the Republic’ Statue Unveiling.” Union Song. Web. 13 Aug 2014.

“The Mac-Paps: Canada’s Forgotten Heros.” On-to-Ottawa Historical Society. Web. 13 Aug 2014. http://www.ontoottawa.ca/index1.html

“Mac Paps Honoured in Ottawa.” Working TV. 13 Aug 2014.

“Mac-Paps Monuments.” The Friends and Veterans of the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion. Web. 13 Aug 2014. http://www.web.net/~macpap/monuments.htm

Petrou, Michael. Renegades: Canadians in the Spanish Civil War. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2008. Print.

Zuehlke, Mark. The Gallant Cause: Canadians in the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939. Vancouver: Whitecap Books, 1996. Print.

© 2014 by Kevin Levangie